Cebo Campbell on Web Design’s Inherent Rhythm

Spherical’s VP of Creative shares his design approach.

Banner Image by Michael Carnevale

Everything has sound. Everything. A lesson learned the summer after I nearly failed English 101 over Lord Tennyson’s poem, “The Brook.” My teacher challenged my classmates and I to read the poem to ourselves. “Euphony,” my teacher professed, was the magic of the poem, and our final was to tell the class what we heard as we read it. Heard, not read. “Listen for the sounds”, she said. Still, I read that poem so many times I memorized the stanzas. And as a teen who obviously knew all there was to know, I could confirm for certain that I didn’t hear anything aside from the classroom air conditioner groaning at the pace of my boredom. Again, I read the poem:

I chatter over stony ways,

In little sharps and trebles,

I bubble into eddying bays,

I babble on the pebbles.

Still nothing. So, to get out of the crosshairs—and to get a grade—I told my teacher I heard a brook. I didn’t, of course. I just read the words in the poem, which filled my head with images and rhyme, but I didn’t hear anything other than the words in my head.

I passed the final and, later that summer, took a trip to the Smoky Mountains near Pigeon Forge, Tennessee. I walked a downhill slope on the seasonally green mountainside. When I reached the bottom, the slope descended to, you guessed it, a brook. My nemesis. I watched the water rush past, skipping over rocks and sediment, freshening the air with chill. Tennyson’s poem rose in my thoughts.

By many a field and fallow,

And many a fairy foreland set

With willow-weed and mallow.

To my surprise, I could actually hear the brook flowing in Tennyson’s words. It was the sound, not just of the words, but how the letters, the consonants and vowels, and the phonetic tone worked together to create a melody—or sound. I heard the Ts as the water chattered over stoney ways, Bs as the brook babbled on the pebbles, and that slow S streaming leisurely through the entire piece. That was it. I heard it. As clear as the water itself. The poem was not just image and meter, but so much more. It was that little revelation that changed everything I thought about poetry, and, eventually, how I approached design.

• • •

Design, whether web or print or even physical spaces, is no different than Tennyson’s poem.

Design has a sound. In its digital architecture, rhythm allows design to transcend a two-dimensional canvas and deeply connect with us beyond imagery through a compositional euphony. In truth, what is rhythm but pattern, a learnable system based on the interrelationship of its component parts? We can channel that system in the way we compose our work. With web design in particular, we can use the canvas to create our own sound, and, in doing so, create a more memorable experience.

There are many tools at your disposal to help develop a sound in your design. Managing space, pacing, color, movement, and disruption will shape your euphony into the style that appeals to your audience.

Space

Sound for the sake of sound is just noise. For it to be something we can discern, sound needs silence, as silence is what activates tone, and keeps sound alone from driving us mad. The same principle applies to negative space in design. In web design, graphic elements function as notes on a sheet of music. Imagery, graphics, typography, and iconography represent those sound notes. The unused space around those elements represent the silence. How those elements (notes) and space (silence) are composed structures the consumption of information. Structural composition is the most important element in creating rhythm in design. Together, space and element make the framework for your sound. This is where the proverbial needle hits the record.

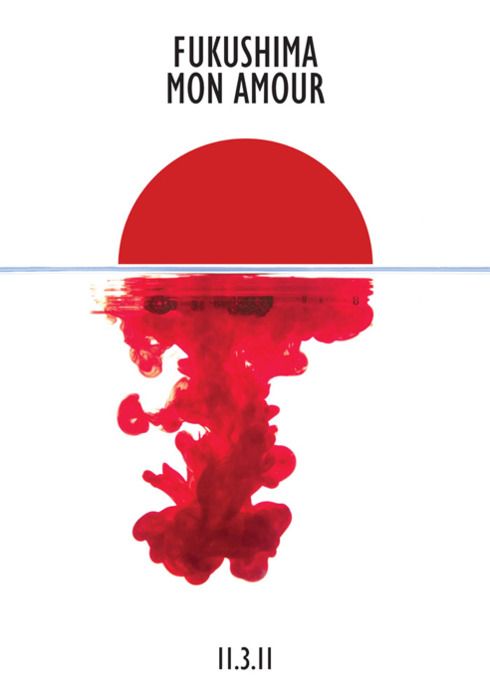

Visually, think in terms of rows and columns, making a grid of squares over a canvas or viewing frame. Screen sizes in web design vary from desktop to mobile will vary, but the principle remains true: the more squares that contain graphic elements–or are colored in–the more sound exists in the frame. The placement and size of those colored squares, stacked atop one another, alternating side to side, or filling large spaces on top or bottom, initiate the rhythmic pattern. Large areas of elements make big sounds, smaller areas make small sounds. Do you want your work to have a booming, dramatic effect or something lighter and mellifluous? If you imagine those colored squares as musical notes, you can actually begin to hear the sound as your eyes navigate the space.

Pacing

Especially in long-form pieces or scrolling websites, the pace with which you deliver your message is the groove. Some people like fast-paced rhythm while others opt for something mellow. If you have a sense of your audience, you can pace your work in such a way that it appeals to them.

If space is the structure, pacing then is the meter. With websites, the typical approach is big header, content area, footer. This is akin to a pop song or a poem in iambic pentameter. It goes does down easy and a user can groove to it without much thinking.

If you aim to do something distinct or novel or even jarring, pacing is where you make that decision, it is also where the story atop the rhythm begins. Pacing is where a piece can feel undulating, repetitive, alternative, gradual, and even disruptive. Cereal Magazine, one of my personal favorites, aligns pace with the content of their written pieces. They deliver smaller bits of copy with loads of space and large imagery to create a sense of a building crescendo as you read through. A similar experience can exist across any medium, from print magazines to interior design. Pacing is the cadence by which a work is both received and remembered.

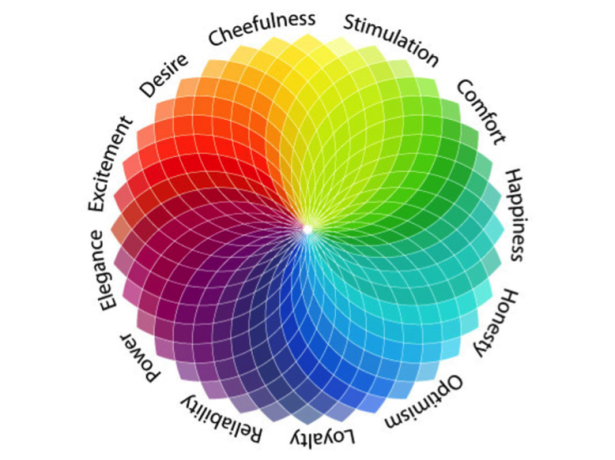

Color

Color in design has enough theory and principle to fill a library of books. There are innumerable choices to make when deciding on a color, so begin, always, with emotion. Rhythmically, color arouses mood, and will be the emotional context of your rhythmic pattern. Are you aiming to inspire cheerfulness, anger, elegance, comfort, optimism? The selection of a color, or no colors at all, can offer an almost lyrical quality to your work through the emotions it inspires.

For example, if your pacing is fast with lots of information shown rapidly, and the tone of the piece is red it might provoke a sense of aggressiveness. If the same is true, but the tone is yellow, the piece could feel zealous. Color is the first rhythmic layer of voice in any work; the first to definitively express intent. Understanding the psychology of color first will help in deciding on a color scheme that best articulates that intent. If space is the structure and pacing is the meter, then think of color as the melody. Color schemes, monochrome, complementary, analogous, and triadic act as a means of communication from the composer to the audience.

Movement

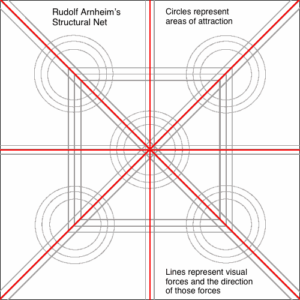

In Rudolf Arnheim’s book, Art and Visual Perception: A Psychology of the Creative Eye, he proposes there’s a structural skeleton behind every canvas that uses a network of forces. The eyes are naturally drawn to certain parts of the canvas. Other diagrams, such as the Gutenberg diagram, the F-pattern layout, and the Z-pattern layout, all suggest a similar notion that viewers assume a natural flow to any work. Take advantage of the movement and increase users’ ability to consume the information you want.

In Rudolf Arnheim’s book, Art and Visual Perception: A Psychology of the Creative Eye, he proposes there’s a structural skeleton behind every canvas that uses a network of forces. The eyes are naturally drawn to certain parts of the canvas. Other diagrams, such as the Gutenberg diagram, the F-pattern layout, and the Z-pattern layout, all suggest a similar notion that viewers assume a natural flow to any work. Take advantage of the movement and increase users’ ability to consume the information you want.

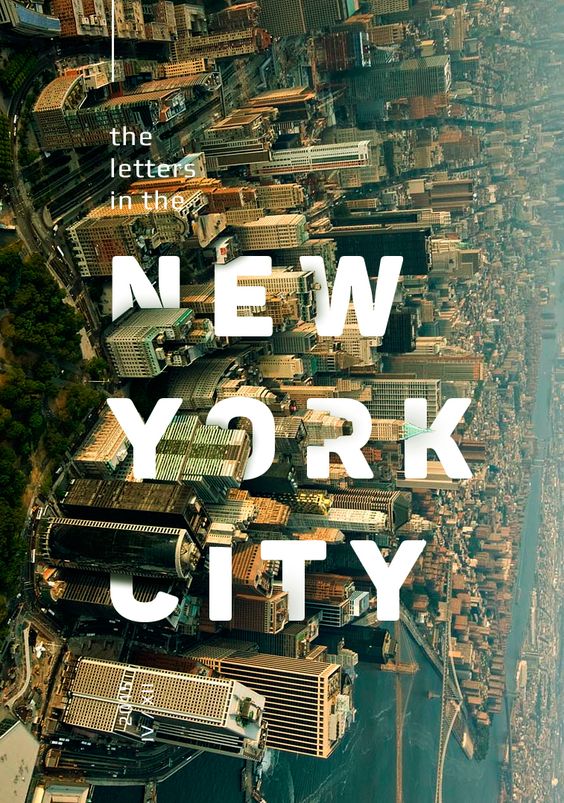

Movement is most closely tied to the overall rhythm as it will force a user to deviate from a pattern to read. It can happen in the use of video and imagery, but sometimes its most powerful impact comes simply from typography and shape. Compositional flow and shape of typography, with knowledge of natural movement patterns, can help you tell your story by presenting information in the right order and at the right scale. Eyes will navigate and consume information in a hierarchical pattern you control. In a literal and figurative way, it is storytelling. In the manner story progresses, undulating peaks of conflict and resolution, appropriate use of typography in a composition can push viewers to the places you want while allowing the most important pieces to shine.

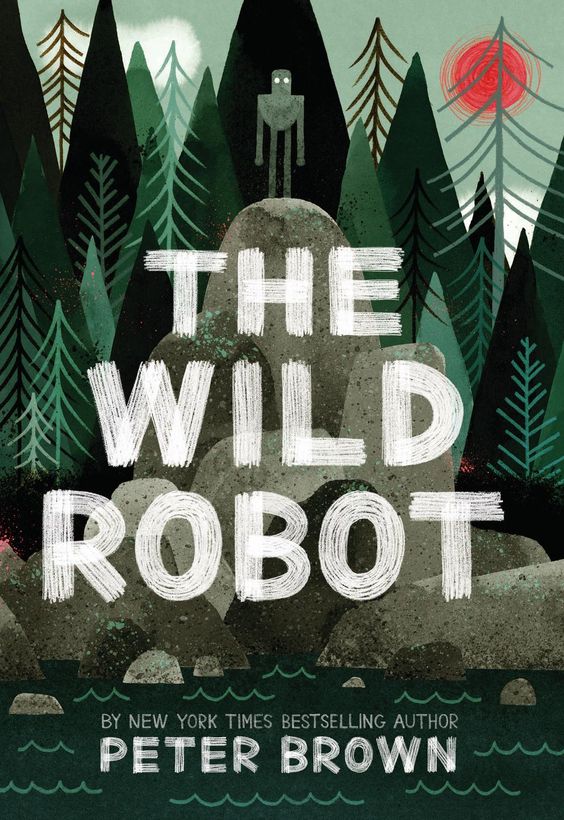

Start with font. Fonts come in myriad types: tall fonts, square fonts, serif, sans serif, handwritten, cursive, and many others. In the same way Tennyson selected words that equated to the sound of water, select a font that helps drive your purpose. Readability, boldness, lightness, cohesiveness, size, and shape should all be considered in terms of how it works with the flow of your work. Using variants in font weights, kerning, and positioning of text can speed up or slow down movement as well a direct it where you wish it to go.

Disruption

Because, why not?

There are times when you’ve decided on spacing, pace, selected a monochromatic color scheme, and a lovely handwritten font that makes for a smooth rhythm throughout your work, and, for all intents and purposes, you decide to just disrupt the whole thing. It is a fine line to walk, and can make for a stunning change in the rhythm.

But be careful. Break pattern in a meaningful way. Contrast, accent, and sudden imbalance can turn a common work remarkable, but can also undermine its intent.

Summary

Everything has sound. There is a music that can be exposed in everything you create. Considering rhythm in your work only taps into something that is omnipresent and imbues it with a familiar force. Rhythm is pattern and pattern is memorable. Try it for yourself. Consider the rhythm in your design as you compose it. Is it groovy, fast-paced, smooth, lighthearted? As a viewer experiences your creation what do they hear? What is the beat thumping in their thoughts or the melody stuck in their head simply by the composition of your work? Because, if you can hear it, so can they.

1706 words

Recent Spherical Articles

Hi